Background

The continuing evolution of the ceramics and materials world and the associated materials technologies is accelerating rapidly with each new technological development supplying more data to the knowledge bank. As new materials and even newer technologies are developed; methods of handling, forming and finishing are required to be devised to maintain pace with this rapid rate of development. One of the most prominent examples of this rapid and accelerating technological development is the electronics industry, more specifically the simple transistor. The pace of this development and the development of the associated materials and processing technology has been quite astounding. The push has been along miniaturisation and packing the maximum amount of performance into the smallest space. Recently noted, an e-mail quote stated that; “If the Automotive industry had advanced at the same pace as the Computer industry, we would be driving cars, which gave a thousand kilometres to the litre and cost $25”. The concept of the simple transistor stands as one of the most significant electronic engineering achievements of the 20th century.

Advances in Ceramic Technology in the Twentieth Century

The 20th century has produced the greatest advancement in ceramics and materials technology since humans have been capable of conceptive thought. The extensive metallurgical developments in this period have now produced almost every conceivable combination of metal alloys and the capabilities of those alloys are fairly well known and exploited. The push for ever faster, more efficient, less costly production techniques continues today. As the limits of metal-based systems are surpassed, new materials capable of operating under higher temperatures, higher speeds, longer life factors and lower maintenance costs are required to maintain pace with technological advancements. Metals, by virtue of their unique properties: ductility, tensile strength, abundance, simple chemistry, relatively low cost of production, case of forming, case of joining, etc. have occupied the vanguard position in regard to materials development. By contrast ceramics: brittle by nature, having a more complex chemistry and requiring advanced processing technology and equipment to produce, perform best when combined with other materials, such as metals and polymers which can be used as support structures. This combination enables large shapes to be made; the Space Shuttle is a typical example of the application of advanced materials and an excellent example of the capability of advanced materials.

Recent Advances in Ceramic Technology

It is only during the last 30 years or so, with the advances of understanding in ceramic chemistry, crystallography and the more extensive knowledge gained in regard to the production of advanced and engineered ceramics that the potential for these materials has been realised. One of the major developments this century was the work by Ron Garvie et alat the CSIRO, Melbourne where PSZ (partially stabilised zirconia) and phase transformation toughening of this ceramic was developed. This advancement changed the way ceramic systems were viewed. Techniques previously applied to metals were now considered applicable to ceramic systems. Phase transformations, alloying, quenching and tempering techniques were applied to a range of ceramic systems. Significant improvements to the fracture toughness, ductility and impact resistance of ceramics were realised and thus the gap in physical properties between ceramics and metals began to close. More recent developments in non-oxide and tougher ceramics (e.g. nitride ceramics) have closed the gap even further.

Properties of Ceramics

Ceramics for today’s engineering applications can be considered to be non-traditional. Traditional ceramics are the older and more generally known types, such as: porcelain, brick, earthenware, etc. The new and emerging family of ceramics are referred to as advanced, new or fine, and utilise highly refined materials and new forming techniques. These “new” or “advanced” ceramics, when used as an engineering material, posses several properties which can be viewed as superior to metal-based systems. These properties place this new group of ceramics in a most attractive position, not only in the area of performance but also cost effectiveness. These properties include high resistance to abrasion, excellent hot strength, chemical inertness, high machining speeds (as tools) and dimensional stability.

Classifications of Technical Ceramics

Technical Ceramics can also be classified into three distinct material categories:

• Oxides: Alumina, zirconia

• Non-oxides: Carbides, borides, nitrides, silicides

• Composites: Particulate reinforced, combinations of oxides and non-oxides.

Each one of these classes can develop unique material properties.

Oxide Ceramics

Oxidation resistant, chemically inert, electrically insulating, generally low thermal conductivity, slightly complex manufacturing and low cost for alumina, more complex manufacturing and higher cost for zirconia.

Non-Oxide Ceramics

Low oxidation resistance, extreme hardness, chemically inert, high thermal conductivity, and electrically conducting, difficult energy dependent manufacturing and high cost.

Ceramic-Based Composites

Toughness, low and high oxidation resistance (type related), variable thermal and electrical conductivity, complex manufacturing processes, high cost.

Production

Technical or Engineering ceramic production, compared to yesterday’s traditional ceramic production, is a much more demanding and complex procedure. High purity materials and precise methods of production must be employed to ensure that the desired properties of these advanced materials are achieved in the final product.

Oxide Ceramics

High purity starting materials (powders) are prepared using mineral processing techniques to produce a concentrate followed by further processing (typically wet chemistry) to remove unwanted impurities and to add other compounds to create the desired starting composition. This is a most important stage in the preparation of high performance oxide ceramics. As these are generally high purity systems minor impurities can have a dynamic effect, for example small amounts of MgO can have a marked effect upon the sintering behaviour of alumina. Various heat treatment procedures are utilised to create carefully controlled crystal structures. These powders are generally ground to an extremely fine or “ultimate” crystal size to assist ceramic reactivity. Plasticisers and binders are blended with these powders to suit the preferred method of forming (pressing, extrusion, slip casting, etc.) to produce the “raw” material. Both high and low-pressure forming techniques are used. The raw material is formed into the required “green” shape or precursor (machined or turned to shape if required) and fired to high temperatures in air or a slightly reducing atmosphere to produce a dense product.

Non-Oxide Ceramics

The production of non-oxide ceramics is usually a three stage process involving: first the preparation of precursors or starting powders, secondly the mixing of these precursors to create the desired compounds (Ti + 2B, Si + C, etc.) and thirdly the forming and sintering of the final component. The formation of starting materials and firing for this group, require carefully controlled furnace or kiln conditions to ensure the absence of oxygen during heating as these materials will readily oxidise during firing. This group of materials generally requires quite high temperatures to effect sintering. Similar to oxide ceramics, carefully controlled purities and crystalline characteristics are needed to achieve the desired final ceramic properties.

Ceramic-Based Composites

This group can be composed of a combination of: oxide ceramics – non-oxide ceramics (granular, platy, whiskers, etc.), oxide – oxide ceramics, non-oxide – non-oxide ceramics, ceramics – polymers, etc. an almost infinite number of combinations are possible. The object is to improve either the toughness or hardness to be more suited to a particular application. This is a somewhat new area of development and compositions can also include metals in particulate or matrix form.

Firing

Firing conditions for new tooling ceramics are somewhat diverse both in temperature range and equipment. This subject is too lengthy to cover here. A wide range of publications is available on this subject for those interested. However, a brief description of some techniques and conditions is appropriate to provide an understanding of the basic technology of advanced ceramics firing. In general these materials are fired to temperatures well above metals, and typically in the range of 1500°C to 2400°C and even higher. These temperatures require very specialised furnaces and furnace linings to attain these high temperatures. Some materials require special gas environments such as nitrogen or controlled furnace conditions such as vacuum. Others require extremely high pressures to achieve densification (HIPs). Thus these furnaces are quite diverse both in design and concept. The typical methods of heating in these furnaces are gases (gas plus oxygen, gas plus heated air), resistance heating (metallic, carbon and ceramic heaters) or inductance heating (R.F., microwave).

Firing Environments

Gas heating is generally carried out in normal to low pressures. Resistance heating is carried out in pressures ranging from vacuum to 200 MPa. Inductance heating can also be done over the same range as resistance. In both resistance and inductance heating the systems do not have to contend with high volumes of ignition products thus can be contained. The typical furnace types used in the foregoing methods are box, tunnel, bell, HIP (gas and resistance heated), sealed (“autoclave” sealed type for carbon element heated), sealed special design (water-cooled type for R.F. heated) or open design microwave heated, (small items).

The Importance of the Firing Process

This brief listing serves to provide an indication of just how diverse the techniques employed to fire advanced ceramics are. Each ceramic type has its own special requirement in regard to firing rate, environmental condition and temperature. If these conditions are not met then the quality of the final product and even the formation of the final compounds and densities will not be achieved.

Finishing

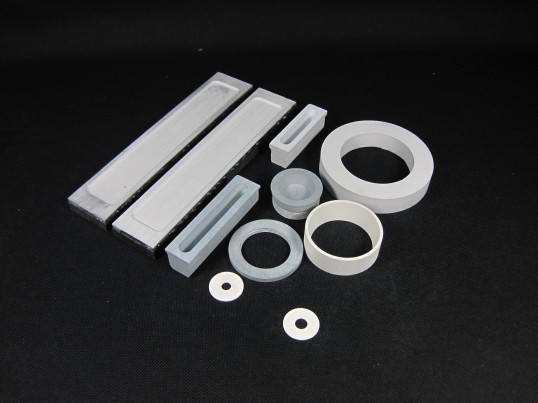

One of the final stages in the production of advanced materials is the finishing to precise tolerances. These materials can be extremely hard, with hardnesses approaching diamond, and thus finishing can be quite an expensive and slow process. Finishing techniques can include: laser, water jet and diamond cutting, diamond grinding and drilling, however if the ceramic is electrically conductive techniques such as EDM (electrical discharge machining) can be used. As the pursuit of hardness is one of the prime developmental objectives, and as each newly developed material increases in hardness, the problems associated with finishing will also increase. The development of CNC grinding equipment has lessened the cost of final grinding by minimising the labour content, however large runs are generally required to offset the set up costs of this equipment. Small runs are usually not economically viable. One alternative to this problem is to “net form” or form to predictable or acceptable tolerances to minimise machining. This has been achieved at Taylor Ceramic Engineering by the introduction of a technique called – “near to net shape forming”. Complex components can be formed by this unique Australian development with deviations as low as ±0.3% resulting in considerable savings in final machining costs.

In many applications today, the beneficial properties of some materials are combined to enhance and at times support other materials, thus creating a hybrid composite. In the case of hybrid composites, it is the availability and performance properties of each new material, which sets the capability of the new material. In-field evaluation testing has to be carried out in certain instances, to determine the long-term durability of the new composite before actually committing to service.

Design

The properties of advanced materials need to be considered when designing structures, components and devices. The final design and material selection must ultimately be cost effective, must function reliably and, ideally, should be an improvement upon existing technology. Prior performance knowledge is obviously an asset, however in many new applications prior knowledge may not be available thus careful observation and recording of performance characteristics of the experimental model, or in plant trial, is needed. In this regard the Materials Engineer works in close contact with the research team to cooperatively develop the new concept. As we are still working with relatively brittle materials this aspect has to be always kept in mind. New techniques such as Finite Element Analysis have proven beneficial in this regard. The use of computer modelling allows the structures to be created on screen without the need for costly prototypes.

Where to next?

Advanced ceramic materials are now well established in many areas of every day use. The improvements in performance, service life, savings in operational costs and savings in maintenance are clear evidence of the benefits of advanced ceramic materials. Life expectancies, now in years instead of months with cost economics in the order of only double existing component costs, give advanced ceramics materials a major advantage. The production of these advanced materials is a complex and demanding process with high equipment costs and the requirement of highly specialised and trained people. The ceramic materials of tomorrow will exploit the properties of polycrystalline phase combinations and composite ceramic structures, i.e. the co-precipitation or inclusion of differing crystalline structures having beneficial properties working together in the final compound.

Tomorrow (even today) the quest will be to pack the highest amount of bond energy into the final ceramic compound and to impart a high degree of ductility or elasticity into those bonds. This energy level has to be exceeded to cause failure or dislocation. The changing pace of technology and materials also means that newer compounds precisely engineered to function will be developed. Just how this will be achieved and when the knowledge becomes public – who can tell! Ceramics, an old class of material, still present opportunities for new material developments.

It is a fascinating quest but this aspect of secrecy and the continued presence of “Black Art” in many ceramic production industries make it even more fascinating.

Note: A full list of references is available by referring to the original text.

Primary author: D.A. Taylor

Source: Materials Australia, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 20-22 January/February 2001.

For more information on this source please visit The Institute of Materials Engineering Australasia.

Enquiry

Enquiry